I learned my knots the hard way as a young crew member on a two-person delivery. The captain asked for a rolling hitch. When he received rolling eyes instead, he reacted by drilling me practically to tears. I was sure he was a sadist, demanding bowlines behind my back and clove hitches on everything in sight. He had me tensioning and loosening lashings with rolling hitches repeatedly for a week. But by the end of the trip, I could reach around the back of a piling and throw in that bowline as easily as tying my shoes. I learned it takes repetition for knot tying to become second nature.

This is not a how-to-tie-knots column. Instead, it’s about the value of using the proper knots. Experienced mariners know how important this is, as pride in the process can create an effortless flow while handling lines. When rigging and securing are done with consistent good habits, teamwork among the crew is improved because everyone is on the same page.

Acquiring these skills takes time. That’s why apprentice boaters really have to apply themselves in the beginning, even if they sometimes feel frustrated. To these people, I simply say practice. Then there’s the occasional shipmate who resists learning to tie knots correctly, perceiving tried-and-true tradition as unessential. He needs to realize that the right knot for the task at hand is essential.

We’ve all heard a shipmate or captain grumble to the whole crew, “Who the heck tied this so-called knot?” Usually, the next few words aren’t pretty. Savvy knot-tying certainly contributes to safety and security, but it also serves to create an unspoken common language among everyone on the boat. In the dark or in a moment of stress when you need to untie something in a hurry, it sure is a relief to discover that someone left you an efficient knot that releases with ease.

When a knot is tied properly, you know just by laying your hands on it, even if you can’t see it. In a challenging docking situation, you might be called on to perform a reliable task in a hurry. This is no time to choke when the captain yells for a bowline. Master your knots and you’ll be well on your way to becoming a respected member of the crew.

When a knot is tied properly, you know just by laying your hands on it, even if you can’t see it. In a challenging docking situation, you might be called on to perform a reliable task in a hurry. This is no time to choke when the captain yells for a bowline. Master your knots and you’ll be well on your way to becoming a respected member of the crew.

Think about it this way: Coils of line and knots are organized systems on a boat. If we all maintain them the same way, the system stays ordered for the next person to use. Good habits promote good seamanship. It’s as simple as it sounds. That’s why we coil three-strand lines in a clockwise direction, twisting the hand to make the line conform to uniform loops, and braided line is often coiled in figure eights. This trains the lines to run out—peel off the coil—smoothly without tangles or kinks. Yes, it looks nice, but the main thing is it functions well.

So, too, with knots. We use the essentials not just because they are traditional, but because they are empirically proven best performers. And, unless you take up marlinespike seamanship as a hobby, you only need to perfect a few knots; they’ll perform for any requirement onboard.

The hitches (half, clove and rolling) are really useful for fixing the line to itself or something else onboard. The square knot and sheet bend are suited to make two ends or lines up together. A figure-eight or favorite stopper knot keeps a line captive where it belongs. And last but not least is the handy bowline, which offers a reliable loop that is guaranteed not to slip or jam. This list makes a fine repertoire for most of us.

Knot-tying is basically a hand-to-eye coordination exercise and for some, it doesn’t come easily. A useful tip is to develop the habit of dedicating one hand to holding the line and one hand to working it. For example, a right-handed person can hold the standing end (fixed or non-working part) with the left hand and use the right hand to shape the necessary loops or hitches in the working end (free portion). In this way, the left hand can function like a clamp, holding things together while the right hand manipulates the rest. This is the easiest way to maintain the mental picture of the desired knot while forming it with the moving parts of the line. With practice, a knot becomes fixed in your mind’s eye.

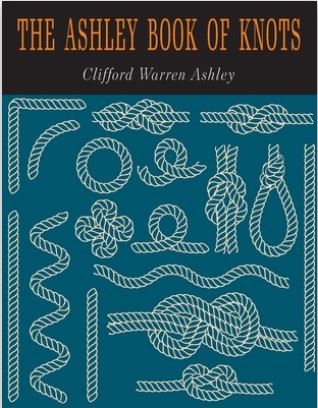

The Ashley Book of Knots has been the seaman’s bible for generations, but I recommend the Internet for a more interactive approach. YouTube has knot-tying videos, some in slow motion, and simple animated illustrations can be found at animatedknots.com.

Whether on the boat or on the dock, cleats are part of the organized system. For most of us it’s already habit, but just in case, it should be made plain that a line should be led once around the base of the far horn of the cleat first. This transfers the load to the bottom of the cleat, closest to the fasteners securing the hardware in place. Then the figure eights from horn to horn secure the line using friction. A twist forms an underhand hitch in the last figure eight to lock the line in place. On sailboats, the locking hitch is used on halyard cleats but omitted on sheet cleats, where an extra figure eight or two ensures a quick release if a sail suddenly needs easing.

There are many ingenious uses of knots and lines. Many are shared by seamen, cargo handlers, riggers and rock climbers. What they all have in common is harnessing the forces of physics—namely friction, vectors of force and mechanical advantage. Once, while I was sailing with a competitive crew in a race, an improperly adjusted genoa sheet fairlead block threatened our edge. The skipper went ballistic, as sometimes happens under racing stress. The load was too great to move the fairlead on the track and it was a long tack we didn’t want to give up. I spent plenty of time on ships stopping off heavy mooring lines and offered to use the same stopper method to take the load off the sheet without changing the shape of the sail.

We tied a half hitch around the base of the sheet winch in the middle of a short length of Dacron that had a rough hand to it, wove the two equal parts back and forth up the loaded sheet in a crisscross snaking pattern, then finished it off with a rolling hitch. We slacked off the sheet, transferring the load to the stopper line. This allowed us to adjust the fairlead block correctly. We winched the slack sheet back in to transfer the load off the stopper again, and voila, the problem was solved without compromising the shape of the sail.

The habit of using slippery hitches is valuable onboard, particularly when it’s cold and wet. When a draw loop is used on the last turn of a clove or rolling hitch, the line can be released quickly with a gentle tug. No struggling with tenacious hitches. It’s perfect for fender lines and quick releases on looped sail ties. Your shipmates will love you for this.

The right knot for the job holds fast under load and is easy to undo, making it reliable and a pleasure to employ. Properly coiled lines will behave beautifully, and cleats that are correctly loaded are less likely to fail. Master these habits, if not for your own pride in seamanship, then for your shipmates. A safe and happy crew makes for a harmonious team. And less cursing.